In the old anecdote, one friend asks another: “Have you solved your problem with incontinence at night? – I’ve been to a psychologist, it’s much better. – Is the incontinence gone? – No, but now I’m proud of it!

I want to tell you why I’m proud of my last place in the Moscow Marathon, which I didn’t even run, but mostly walked fast. And why I consider this result to be my big win.

But first – a bit of detail about the challenge.

Marathoner

The length of the marathon distance is 42 kilometres and 195 metres. And that’s a lot.

By comparison, the length of the Third Ring Road, which encircles Moscow within its historic boundaries, is 35 kilometres. The maximum distance the Roman infantry would cover in a day by forced march is 45 kilometres. At 40 kilometres above the surface of the Earth there is no more air, no more blue sky and it is clearly visible that our planet is round. The width of marine areas, over which states have control under international law, is 44 kilometres.

In conventional terms, anything close to 40 kilometres is in some sense a border distance.

Felix Baumgartner parachuting out of the stratosphere from 39 kilometres on October 14, 2012. Source: telegraph.co.uk

According to the official sports classification, the marathon is an ‘ultra-long distance’ and it is four times the ultimate ‘long’ distance of 10,000 metres.

It can also be called ultra-long distance because it puts the human body under extreme strain.

This is a partial list of the complications that a marathon threatens runners’ health:

– Scarring of the heart muscle,

– Weakening of the thyroid and adrenal glands,

– Inflammation and degeneration of tendon tissue,

– Deterioration of fat metabolism in the body,

– Reduced bone density,

– Depletion of muscle tissue.

In general, the marathon is by no means about comfort and health. Not coincidentally, legend has it that the first man to run this distance died as soon as he reached his goal.

On the other hand, the marathon reveals a part of our nature that is rarely called upon in modern urban life – exceptional endurance.

Some scientists insist that humans as a species are not at all as weak as is commonly thought. For example, Nikolay Amosov, Doctor of Medicine and promoter of a healthy lifestyle, believed that civilization has simply freed us from the need to develop our physical qualities to the limit. But we are in no way inferior to animals in them.

The longer a human being competes with a horse, the less chance the animal has of winning.

Amosov’s view is confirmed by the results of a human-horse race, held in England since 1980, in which runner and rider compete over a distance of 35 kilometres. The horse wins most of the time.

But, firstly, not always. Secondly, the runners are usually only minutes behind the riders. Thirdly, a horse in a race is guided by the will and intelligence of the rider, which makes it more efficient than ordinary animals. In any case, these races show what exceptional endurance is inherent in us from birth. And the marathon is a practical demonstration of this ability in humans – provided, of course, there’s enough training.

Training that I don’t have yet.

Who am I?

I’m 39 years old. I’ve never been systematically engaged in sports, let alone run. By education I’m a humanitarian. I have always made a living from intellectual work, during which I used to sit and sometimes even lie down (I have been suffering from back pain for years). I have been overweight since childhood. When I decided to start changing at the age of 37, I was 3rd degree obese and weighed 152 kilos.

My work on myself started on February 7, 2019. First I fixed my diet and for a few months I just walked outside for a few hours every day at a brisk pace. Then I got on the elliptical and started working out hard on it. So a year passed. During that time, I lost 50 kilos.

If someone had told me the version on my left that I could finish half marathons and marathons in a couple of years, I would have wagged my finger at my temple.

In February this year – 2020 – I started running on an electric treadmill. Since May, I’ve been running on the street. But I haven’t abandoned walking: I use it for warming up and warming down, and also practice Nordic walking with poles. I try to train at least five times a week for 40 minutes to two hours.

As a result of such training this year I was able to run – precisely to run without changing to a step – two half-marathons a week apart: in Moscow on 02.08.2020 and in St. Petersburg on 09.08.2020. Not too fast (or rather, frankly, slow): in Moscow – in 2 hours 22 minutes, in St. Petersburg – in 2 hours 18 minutes. Still, considering the short period of my training, I was very pleased with these results.

By the standards of amateur sports, I’m a neophyte: I don’t have a well-trained body, I weigh a lot (about 100 kilograms), I don’t have proper running skills, my cortex muscles are weak and my coordination is poor. People with such data have no business running a marathon. If someone in my condition came to me with the question “should he or she run a marathon or not?”, I would 100 per cent discourage them.

But in my life, I often succeed in schemes: “It’s impossible, but you have to try.” So I decided to try and “hack” the Moscow Marathon with the modest data I had on hand. And, unexpectedly, I succeeded.

“Think, Fedya! Think!”

I confess, I don’t like the modern fitness industry. First of all, because of the cult of stupid, linear achievement, which is found in it all the time.

“Desire the impossible! Strive as hard as you can! Move while you can! Don’t think you can do it! If you succeed, good for you, that’s how it should be! If you don’t make it, clean yourself up and keep pushing! “If you bang on a closed door, you’re a pussy!”

This approach seems to me silly and unproductive. First of all, because the result cannot be clearly predicted.

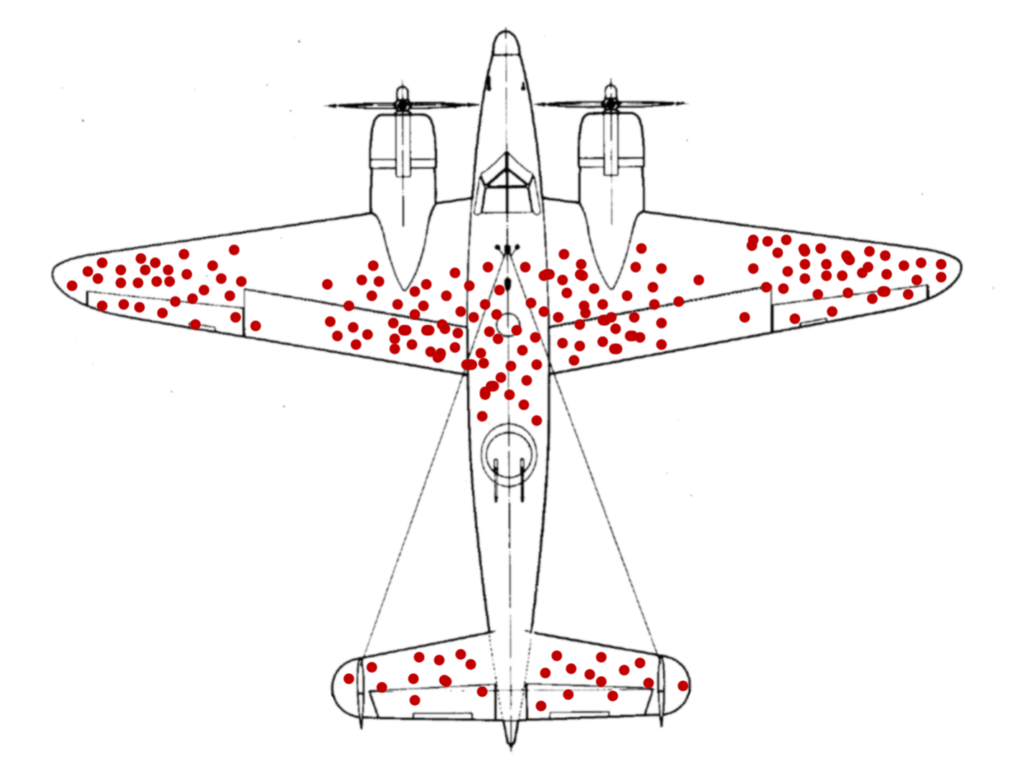

My work in business has taught me that success only becomes a personal achievement when it is rationally predictable. Those who simply run around with their heads down are exposing themselves to unnecessary risk. Those who mechanically try to replicate others’ successes without considering the negative experiences of those who have failed, hold themselves hostage to the statistically famous “Survivor’s Error”. (Wikipedia article “Systematic Survivor Error”)

The concept of “Survivor Error” originated when mathematician Abraham Wald proved that damage to aircraft returning to a military base does not need to be protected as much as damage to aircraft that die on departure.

So my preparation for the marathon began not with training but with analytical work.

Marathon code

The data I started analysing was, I confess, so-so:

The length of the marathon is 42.2 kilometres.

Its ideal time for an amateur is 3 hours (running a marathon in three hours is every non-professional runner’s wet dream).

My best time at the half of this distance was 2 hours and 18 minutes.

It turned out that even if I could run the whole marathon at the speed I developed at the half marathon in St. Petersburg, I would cross the finish line 4 hours and 40 minutes after the start. Almost two hours later than the “ideal time”. Which is not cool at all. And this despite the fact that I finished in St. Petersburg on my last breath, so it would have been ridiculous to expect to double that result after just a month.

Having carefully considered this data, I decided not to commit to a time with which I would overcome the marathon at all. My logic was as follows: “The race is officially six hours long. So, I would just have to meet this time in order to be successful. And it didn’t matter what minute I’d be at the finish line”.

If you divide the 42.2 km distance by 6 hours, you have a speed of 7.1 km/h – the minimum speed at which you can run a marathon. This is very low for a runner and high enough for a pedestrian.

School textbooks assure us that the average speed of a pedestrian is 6 km/h. In fact, I have observed that nowadays people walk no faster than 5 km/h, even when they are in a hurry. If I decided to walk a marathon at a fast pace, I would have to walk for 6 hours without stopping at a constant speed of 7.1 km/h without slowing down for a minute, which is not an easy thing to do.

But my wants didn’t end there. I was categorically not ready to repeat the St. Petersburg experience and finish barely alive. I wanted to conquer the marathon with my health and strength intact to be able to enjoy the victory.

At the finish line of the St. Petersburg half-marathon it was very hard for me. The short break after the Moscow half marathon, the hot weather and a lot of climbs on the course affected me.

Having considered this and that, I decided that it was more likely that I could achieve what I wanted if I alternated between slow running and fast walking in the marathon, doing it at a comfortable, not too high, heart rate.

That’s what I did.

Let me be clear right away: I didn’t sit with a compass over a map and calibrate the optimum distance for running or walking. I decided to deal with this on the spot. And I did.

I ended up running a total of about 17 kilometres in four sections over the marathon, spending just under two hours. The rest of the distance I walked at a brisk pace. The journey from start to finish took me 5 hours and 55 minutes, a time that matched my calculations perfectly. I finished running, feeling as well as I could in such a situation.

And yet, if I say that I easily conquered the marathon, being confident of success from the first minutes, I would be lying.

How it was

For two months before the marathon, the thought that at some point I would have to go to the start did not even make me shiver, but a kind of emotional stupor. It’s like being at sea when you’re bobbing on the waves in the wind and suddenly there’s a berm the size of a small house looming over you. And you understand that there is no way you can swim in it, so you have to duck under the wave and calmly wait for it to turn and toss you from side to side. And pray during that chafing that you don’t get hit on the bottom or killed by some random rock.

The same feelings were evoked in me by the marathon.

I was not afraid of its approach, I was not wrapped up in positive motivations, I just felt like something huge and cruel was coming towards me. I tried to have a minimum of emotion about it.

I didn’t even train for a couple of weeks, following the principle “you can’t breathe before you die”. I just lived, saved up my strength and tried not to think about what was to come. Even my family did not know for sure if I would run the Moscow Marathon or not. They knew that I was registered for it, though.

On the morning of September 20, I went to Luzhniki, taking along my sports gear and 8 packs of energy gels with 100 kcal each. I changed my clothes and took a place in cluster J, the last cluster in the start line, where the people who were aiming for the slowest result had gathered.

The route of the Moscow Marathon encircled the entire city centre this year.

The marathon started on schedule at 9am and elite athletes were the first to run. Our cluster started at 9.30. At this point I was still trying not to think about the huge distance I had to cover. To distract myself from these thoughts I started to listen to a selection of Latin American songs that I sometimes play during training. I listened to them on my regular wired headphones plugged into my phone, which was in my jogging belt.

I got off to an easy start. I fell on the tail of two pacemakers, who were leading the crowd in 4 hours 59 minutes, and safely ran 10 kilometres with them. We ran Luzhnetskaya Embankment, Novodevichy, Smolenskaya, Krasnopresnenskaya and Krasnogvardeisky Passage. But when, at the turnoff from Mantulinskaya Street, the long and steep hill of 1905 Street loomed before us, I knew it was time to start pacing.

Psychologically it was not easy. I was not tired and could run on. And I remembered the disdain with which, at the St. Petersburg half marathon, I myself looked at people switching from running to stepping. Alas, this is an inevitability: when you don’t allow yourself to show weakness, you are forced to distance yourself emotionally from those who you think have already given up. But at that moment, when I started to walk fast at the Moscow Marathon, I was not driven by cowardice, but by cold calculation.

I understood that there was no guarantee that I would be able to run at this pace for the full 5 hours, so there was no need to take any risk. It was also clear that I would encounter many hills and inclines on the way, and I would not be able to overcome them running. So as soon as we reached the mountainside of 1905 Street, I started walking.

Of course, this does not mean that I relaxed and stopped trying. By running I had gained a head start for walking and had no right to waste it on rest. So I tried as quickly as possible to switch to a stride pace that guaranteed me a successful finish as if I wasn’t running at all – 8-8.5 minutes per kilometre.

At the start, I ran a running workout programme with an active GPS chip on my sports watch, and the dial constantly started to show my current pace. I moved with this data in mind.

I walked up 1905 Street, turned onto Krasnaya Presnya, reached the Garden Ring, turned right, went through the tunnel under Novy Arbat, reached the Park of Culture and went up to the Krymsky Bridge.

I moved the way I was used to walking during my long walks and Nordic Walking classes. I leaned forward slightly, stepping resolutely on nearly straight legs, waving my arms, trying to achieve a pendulum effect in the alternation of legs, when it seems that the body itself was carrying you forward, forcing you to keep moving.

All the while I was being overtaken by runners who seemed to be looking at me disapprovingly. But I kept going at my own pace, trying not to pay attention to anyone.

Somewhere around Smolenskaya-Sennaya Square I noticed that everyone who could, had overtaken me and there were few people around. I was catching up with the tired and lagging runners at about the 32nd kilometre and so my journey continued with only a handful of hitchhikers.

And then I discovered an unexpected advantage of my marathon tactic: the ability to walk through the empty centre of Moscow during the day. For several hours in a row, I walked along the capital’s car-free, almost deserted roads. Where, at normal times, a pedestrian would have no chance of being without danger to life. I went down into tunnels under avenues. I’ve walked across empty bridges. Walked embankments and main streets. My journey was reminiscent, in every detail, of the setting of a post-apocalyptic movie or computer game. Except that it was actually happening. It felt amazing! I was so encouraged by this discovery that I raised my pace and started dancing to the rhythm of the Latin American melodies that were ringing in my ears.

This is roughly how I saw Moscow during my marathon.

Just because I enjoyed the experience does not mean that the path was easy for me. The marathon pace of walking demanded total concentration and constant effort. If I was distracted by thoughts or relaxed a little, my speed immediately dropped and I had to catch up immediately.

I strove to completely dissolve into the rhythm of the walk: I was not distracted by the greetings of the volunteers standing along the course; I did not slow down, taking water at the drinking points, moving along a smooth path; I did not react to any external stimuli.

Twice during the marathon this concentration played a cruel trick on me. The thing is, the whole time I was moving I was really hungry. I, of course, sucked down a bag of energy gel every four or five kilometres. But that was not enough: my body was begging for solid food. Bananas would be best for a snack on the go, but due to my concentration I missed the opportunity to get them on the course twice.

The first time it happened on Krymsky Val near the Park of Culture. There was a water distribution point there. I took a bottle and kept walking. After about 15 metres, at the entrance to the tunnel in Oktyabrsky I came across piles of yellow skins and half-eaten bananas lying on the pavement. This is how I realised that I had missed the food distribution. Of course, I didn’t go back for it and continued down the banana littered road.

It was an epic sight, I must say: on a white day you descend into an empty city tunnel, with a ton of banana skins and under-eaten bananas lying at the entrance from runners who had been there before you. 100% immersion in the setting of the Planet of the Apes world.

The second time the same mishap happened to me a couple of hours later on the descent from Staraya Ploshchad to Kitaygorodsky Proyezd. A couple of young lads were walking towards me, waving their arms. I assumed they were motivational volunteers, so I ignored them. It was only as I neared them that I noticed with my side-eye that they were handing out bananas, which at that moment I really needed. Again I didn’t slow down or call out to them so as not to lose my rhythm.

The secret ingredient

If there was any secret to my marathon completion it was inner concentration.

When someone I know who knew me back in the days when I couldn’t walk a couple of blocks (and that was only a year and a half ago) asks me how I manage to train for a couple of hours every day now, I tell them a tale from the 18th century French philosophers:

“The Marquise du Deffan, a friend of Voltaire, a lover of philosophy and mistress of a fashionable salon, once had a conversation with Archbishop Melchior de Polignac about Saint Dionysius of Paris. The archbishop said that when the pagans beheaded the saint, he rose to his feet and, holding his own head in his hands, made his way to the site on which the cathedral was later built.

– Just imagine, he never let his head out of his hands,” repeated the bishop, colourfully describing how difficult the journey had been for Dionysius.

To which the Marquise wittily remarked:

– ‘In such a situation the hardest thing to do is to take the first step.

In Soviet books this story was presented as an anti-religious satire. To me, it always seemed deeper than it might first appear.

Indeed, if you open yourself up to an impossible act, it doesn’t matter how many steps you take in the direction of the goal. In fact, all along the way, you will simply have to repeat your first step as many times as it takes to succeed.

Dionysius of Paris is still depicted in icons, frescoes and illustrations, striding with his severed head.

Even today, with my marathon story behind me, I don’t fully believe I can overcome that distance. Especially when you remember my past background and years of disdain for any physical activity. But I have already achieved it. It was enough for me to take one step from the start to the finish line and then just repeat it about 50,000 times at the right pace.

This, I think, is the main advantage of cyclic sports over strength sports. During long endurance training, it’s as if you place yourself at the centre of the universe, and then the movement of the universe adjusts to the pace of your body. This is particularly evident in the inner experience of time while walking or running: the monotonous repetition of the same actions slows down the perception of time in your head, subordinating it to the rhythm of your breathing and movements.

According to my internal clock, the marathon lasted about a couple of hours for me, because I managed to withdraw my thoughts into myself and almost stopped thinking about extraneous things, allowing my body to move automatically. It was very similar to the state when you lie awake in bed at night, but with your eyes closed, and breathe quietly, slipping into a light doze.

At the same time, of course, I reacted to my body’s experiences and everything that was going on around me, adjusting my activity with this data in mind.

For example, I drank at almost every water point. Not much: 3-4 sips each. This made me want to go to the toilet several times during the marathon. I took it as an inevitability. I calmly waited for a toilet cubicle with a straight stretch of road behind it, entered it, rested for 40 seconds, then started running for 2-3 kilometres, making up for the lost time and earning a new head start. Then he would switch back to a brisk pace.

“You won’t make it!”

Of course, my journey was not without its difficulties and unforeseen hindrances. Here are the main ones:

The weather (which turned out to be very changeable)

In the morning before the start it was freezing outside. Then the sun came out at the marathon and it got hot. But when the sun disappeared behind the clouds, it got cool again. This was especially felt on the embankments, which were blown by a sharp wind from the Moscow River.

As a result, by the finish line I was so cold that I spent about 40 minutes under a hot shower at home to thaw out.

The track topography

Already on the course I learned from people running nearby that the Moscow Marathon is considered by runners to be a difficult route because of the hilly terrain. I most remember the endlessly long and steep ascent from the Moscow River along Yauza, Pokrovsky and Chistoprudny Boulevards to the Rozhdestvensky Boulevard. But there were enough ascents and descents along the way. If I had dared to run up them, they would have killed me for sure.

Fear of being late

Of course, my greatest fear was not being on time for the finish line. And I was severely punished for that fear.

There were flags posted along the entire marathon route indicating the kilometres covered. In the middle of the course, on the Bolshoi Ustyinsky Bridge, there was a large clock next to the flag indicating the elapsed time.

Imagine my horror when I saw the time of 3 hours and 20 minutes on it. That was my verdict: the clock showed that I would not be able to meet the 6-hour time limit. I would have to complete the second half 40 minutes faster than the first half to be able to finish successfully, which was absolutely unattainable for me.

I got discouraged. If I had been a little more impressionable, I would have quit the course immediately. But I continued at the same pace as before (even though I thought it didn’t make sense at the time) and began to check my calculations in my mind, trying to figure out where I had gone wrong. It looked like nowhere.

It was only when I reached Luzhniki that I remembered that our cluster started running half an hour after the start of the marathon. The clock on the bridge was counting down the total time of the event! I was not down by 20 minutes! On the contrary, I had 10 minutes to spare, which could have turned into 20 by the finish if I had repeated the time of the first half of the marathon.

Of course, this answer lay on the surface. But by the time I encountered that damned clock, I’d already been moving at full speed for about three hours without a break. No wonder I’d managed to get it so wrong. Exhaling, I continued pacing further. The plus side of this incident for me was that I was once again convinced of the principle: any seemingly obvious thing should be tested by analysis.

I went blind.

The second event that almost threw me into panic was the sudden death of my sports watch. At kilometre 25, it simply switched off and I lost the ability to track my pace. At first I thought there was a system failure. But then I realised it was my fault.

As I said above, immediately after the start I activated GPS mode on the watch to record my movement on a map. It’s a very energy consuming function. But along with it, the watch left on constant vibration mode, which I use to learn how to control my step rate in training. Of course, after three hours of this wear and tear, the watch went out.

But I wasn’t particularly happy when I realised that the clock was OK: I was frantically trying to work out how I was going to make it through the remaining 27 kilometres on time without monitoring my pace. I had to come to terms with it, rely on my internal sense of rhythm and try to pace as fast as I could.

I wouldn’t have been so blind if, apart from the kilometre flags, I’d have met the town clock regularly along the way. Then I could have counted my pace in my head. But it turns out that street clocks have all but disappeared from Moscow’s roads today. Walking from Tsvetnoy Boulevard to Luzhniki I met them only four times.

One could try to catch the fast rhythm of Latin American songs that were playing in the headphones. But by the end of the third hour of the marathon the music had tired me out and began to slow me down. I was forced to take the headphones out of my ears and walk the rest of the way in silence, purring rhythmic melodies under my nose.

Another pain: because my watch went off at kilometre 25, I failed to earn myself the “40,000 steps a day” badge in the sports app that I had long dreamed of.

A bloody trainer and a T-shirt-knife

My journey was not without self-mutilation.

About 15 kilometres before the finish line, my right trainer started rubbing on my heel. I got it wet while rinsing my hands from a bottle of water on the move, and it immediately became rough and hard. Actually, I usually take a band-aid with me when I leave the house for a run. Always, except for that one morning in my life when I went for a marathon.

It was clear that within minutes this chafing would turn first into a blister and then into a bloody wound. The only way out was to approach the medics who were on duty along the course in the ambulances and ask them for a band-aid.

But, as luck would have it, there were no ambulances in my vicinity at that very moment. So I decided to let the pain go, reasoning that since the trainer had been fitting me for the past months, it would not cut my foot deeply with its edge, but would simply remove some skin and meat from the top edge of the heel. And so it did. The wound was the size of a ten-rouble coin and hardly interfered with my walking.

About the time I came to terms with the discomfort of a wet trainer, my sweat-wet T-shirt began to chafe. It happened in a very unexpected place: the front of my left armpit. Listening to my body’s sensations, I realised that the T-shirt was unluckily pulled on by the jogging belt I was wearing over it. I had to take it off, roll it into a knot and carry it further in my hand or pocket. It wasn’t very comfortable, but it saved me the trouble of sharp creases.

Hunger

The last difficulty I encountered at the marathon was hunger. You can rest assured, having lost 50 kilos, I had had time to learn all sorts of feelings of not being satiated. But this was different. The marathon opened up some kind of animal dimension of hunger in me and with it an animal flair for finding food.

It was probably a legitimate thing to do. I spent about 5,000 kilocalories on the marathon in 6 hours of uninterrupted movement. 800 kilocalories of which I made up for with sports gels. I ate 300 kilocalories for breakfast: oatmeal, banana and coffee with milk. I had a deficit of 4000 kilocalories, which is the average dietary intake for two days. Logically, I was always hungry while moving.

It was amazing how my body reacted to this hunger. I didn’t feel dizzy, my stomach didn’t cramp, I didn’t lose strength. My sense of smell was just incredibly heightened. I began to distinctly discern, in minute detail, the smells from the restaurants I passed or ran past. It was definitely not a hallucination. I could first smell food – pizza or roast meat – and then find the place where it was coming from with my eyes.

In the last quarter of the marathon, Pepsi Cola helped me a lot with my hunger. Bottles of it appeared on the tables next to the water. It was a classic Pepsi Coke, full of sugar and caffeine. I drank two or three of them and felt much better.

Around kilometre 40, I finally got the banana I’d been dreaming of all along the way. I don’t know how a person’s biochemistry behaves in such a situation, but it seemed to me that I crossed the finish line running thanks to the energy of that banana.

The bus of death

Another striking impression I had of the marathon was of the bus, or rather the buses (there were two) that followed the convoy of runners and collected those who didn’t meet the time limit.

I knew I was going to see this mechanism and started calling it “the bus of death” beforehand. The first time I saw this convoy of two buses was near Novopushkinskaya Square: they were pulling into Tverskaya Boulevard, and I was already turning off onto Tverskaya Boulevard.

They were plain white buses, like sightseeing buses. They moved slowly and inexorably.

Now I can see from the map that we were separated by as much as two kilometres. But at that moment, it felt like the death bus was almost behind me. “The death bus is coming for you! The death bus is coming for you!” – I kept repeating to myself, and trying my best to pick up the pace.

These buses terrified me, like an indifferent and ruthless killer in a thriller. But they were also slightly amusing, because they reminded me of Pacman or Serpentine from the eight-bit games of my childhood.

The second time I saw this column was on the Kotelnicheskaya embankment next to the high-rise. I was already heading towards the Luzhniki, and they were still going in the direction of Gonchariy proezd. Before my eyes the “death bus” came up to the girl, who could hardly move her legs. It stopped.

A stern woman, wearing spectacles and carrying a folder, looking like a school head teacher, got off the bus. At the sight of her, the jogger made a jerk, like the agony of an antelope falling into a ravine with crocodiles. But the head teacher stopped her with a determined cry:

– Young lady, get on the bus! You’re not on time. The marathon is over for you.

I did not see whether the girl acknowledged the authority of this unforgiving lady, or whether she began to bicker. I simply quickened my pace, repeating, like Benedict in Tatyana Tolstaya’s “Kysy”: “God forbid, God forbid. I am not ill, I am not ill, no, no, no. Don’t come, don’t come, don’t come…”

Finish

Somewhere around kilometre 35 I had a feeling I could finish on time.

I could see that I wasn’t losing my pace, I noticed from the street clock that I was on time, the “death bus” wasn’t breathing down my back and I still had energy left.

By this point my exertion had peaked and I had turned into a pacing machine. The marathon had already lasted more than five hours for me. To keep my head still, I started mapping out on the course the targets I had to reach and endlessly scrolling through their names in my mind to the rhythm of my breathing and steps.

“37-38”, “37-38″… – for the 37th and 38th kilometre marks. “39-41”, “39-41” – when the 38th kilometre was left behind. For about an hour and a half, only the numbers sounded in my head.

If the bulk of my walk through the empty city resembled the setting of a disaster movie like The Day After Tomorrow, near the end of the marathon I found myself inside a TV series called The Walking Dead. All around me, with a struggling leg, were dozens of runners who were exhausted, but still eager to finish.

For some reason, only a few of them were trying to make the transition to brisk walking as a full-fledged form of transportation. Most, waddling, gathered their remaining strength and suddenly started running, only to burn out after 10-15 steps and almost stop again.

According to the marathon administration, out of 9,800 athletes who started the Moscow Marathon, 400 could not finish. Some of them simply walked off the course. Someone was taken away by the “bus of death”. But I think I managed to catch up with most of them and saw them in the last kilometres of my journey.

For the most part, they were people like me: not too young, not too trained, but they were all united by incredible tenacity.

I remembered a grey-bearded and heavy man of about 50, who, like me, was walking to the finish line at a brisk and determined pace, while a young girl (probably her daughter) was riding her electric scooter in front of him and was encouraging him in every possible way. It was a very touching picture.

There was a very positive vibe among the zombies: everyone was motivating each other, smiling, and when one guy in front of me got a leg cramp, two people immediately rushed to help him.

This was in contrast to the war of all against all, which I later found out was waged by the elite athletes competing for the prizes. The finish of the marathon was marked by a scandal when the winner, Yury Chechun, made an obscene gesture to second-placed Iskander Yadgarov.

The finalist Yuri Chechun tried to humiliate Iskander Yadgarov, the Moscow Marathon silver medallist, at the finish line. The incident escalated into a media scandal with mutual insults.

Four kilometres before the finish line, I was faced with another difficult choice: run or walk. On the one hand, I definitely had the strength left for the final spurt. I could try to win back an extra 15-20 minutes by running.

On the other hand, it was clear that I would meet the 6-hour mark if I just kept walking at a brisk pace. So I decided not to take any chances: it was unclear how my body would react to running after five and a half hours of movement. For example, I might stumble, or my leg might cramp up, or my blood pressure might spike.

And although the volunteers at the last kilometres, seeing how determined and alert I was, shouted “Run! You can do it!” I did not give in to their urging and ran only the last 200 metres to the finish line, to please myself and the few spectators who were still there.

To be honest, my cheerfulness in the last minutes of the marathon was contrived. I wanted more than anything to lie down and go to sleep at this point.

When my feet crossed the finish line of the Moscow Marathon in 5 hours and 54 minutes and 48 seconds after the start, I felt like Captain Jack Sparrow from the first part of Pirates of the Caribbean. In that episode where he approached the city waterfront on a tiny sinking schooner and took a step onto the dock just as the ship went completely to the bottom. So did I, cheerfully and cheerfully finishing in the final minutes of the marathon. And was incredibly happy about it.

Life after the marathon

At the finish line I received my participant’s medal. I wrapped up in a foil blanket kindly offered to me by the volunteers, grabbed a couple of bananas at the feeding point, two bottles of water and started getting used to the idea that I had done the unbelievable. At 39 years old with no years of sport under my belt, I have run a marathon.

As you can see from this screenshot, I was not the very last person to finish the Moscow Marathon: fifty more people finished after me. But considering that about 10,000 athletes took part in the marathon, my result is still very, very modest.

I must admit, I felt a lot better than I did after the St. Petersburg half marathon. And that was the first wisdom I got from the marathon challenge.

In St. Petersburg I ran a distance of 21.1 kilometres. I ran it in the heat, with as much speed as I was capable of. When I finished 2 hours and 18 minutes after the start, I felt terribly ill. I was nauseous, I had a headache. I couldn’t even celebrate my success because all I felt was powerlessness and pain. And that, again, with a result of 2 hours 18 minutes for 21.1 kilometres.

At the Moscow marathon I crossed the middle of the distance – the same 21.1 kilometres – in 2 hours and 40 minutes after the start. After that, I covered another three hours continuously, covered the same distance, finished running and feeling quite decent.

That’s how I understood that it wasn’t the half-marathon distance that nearly killed me in St. Petersburg, but the high speed and high heart rate at which I ran in order to win back those miserable 20 minutes. A time that didn’t fundamentally change anything for me in essence. It’s true what our ancestors used to say: you drive quietly, you’ll be further away.

So, I finished. Tired, cold, hungry, with a bloody leg. But with a clear head, no high blood pressure (before my watch died, it was showing me a heart rate of 120-130 beats per minute. I think it was about the same at the finish line). I had no knee pain, no back pain and no joint problems at all.

But right at the finish and for five days afterwards, I had wild meat aches all over my body: thighs, buttocks, calves, shoulders, back, even my neck. My right trainer was soaked with blood from a heel wound. My windbreaker was white on the outside from the perspiration. I was wildly hungry, sleepy and wanted nothing more to do with any sporting activities.

I should mention that this feeling was still with me a week and a half after the marathon. I don’t feel like participating in any long races or hikes just yet. So I went back to training on aerobic machines at the gym.

My next goals in working on myself: to get ready for the TRP and to cut the weight by 10-15 kilograms. After the marathon and half-marathon I felt the need to lose weight so that I could more easily endure the long strain of running and walking.

What was the need for all this?

When people ask me why, at my age, I needed to run half marathons and torture myself with a six-hour marathon, I crack a joke: Why does Putin fly with the Siberian Cranes? Because he can.

But seriously, there were three reasons for my heroism:

1. I didn’t want to feel sick and didn’t want to look disabled in my eyes

Third-degree obesity is severe. In fact, this diagnosis means that you are a handicapped person (simply put, disabled): you have difficulty walking and breathing, you have constant pressure problems, joint pains, and you are tormented by mood swings. On top of that, you are constantly discomforted by the way you look and the way other people react to you.

But the last thing you are prepared to feel in this state is to admit that you are sick and infirm. If, at the start of my work on myself, I began to look at myself as a patient who needs to lose weight at the cost of a monstrous effort, only to become one of the everyday people. With a modest tummy and a measured life, I absolutely would not have gone that route.

Big things require ambitious goals. That’s why from the first days of working on myself I immediately strived not just to improve my shape, but to surpass most people around me with my physical qualities and skills to use my body.

And this aspiration kept me going day after day.

The marathon was an important outcome of this project of mine.

2. I wanted to experience and demonstrate to those around me the limits of walking

During the time I have been developing and strengthening my body, I have noticed a dismissive attitude towards walking among runners, fitness enthusiasts and ordinary citizens. This is despite the fact that walking is an Olympic sport and a full-fledged athletic activity, which has a number of advantages over running or working out at the gym.

As a result, after just one year of regular exercise, I was able to run a marathon, which would have been absolutely impossible if I had only been running.

3. For fun

I’ll repeat the statement with which I began this text: marathons are never a story about health.

Yes, marathons are used to promote a healthy lifestyle. And the people who run marathons are usually healthier than those who watch them. But marathons themselves are by no means health-promoting. At best, they don’t harm it.

When it comes to the benefits of running, Kenneth Cooper, American physician and iconic author of the aerobic exercise theory, has concluded through years of research that an adequate and necessary running distance for health is only 5 kilometres.

But just because marathons don’t prolong our lives doesn’t mean they’re bad.

“Anything, anything that threatens doom,

“To the heart of mortal man

“The inexplicable pleasures

“The pledge of immortality, perhaps!

And happy is he who, in the midst of excitement.

“He could find and know them.”

Personally, the idea of an endless earthly life disgusts me. And I am more worried not about the duration of my bodily existence, but about its quality. Therefore, it makes no sense to me to strengthen my health by jealously guarding it. It’s like building a race car in your garage and then keeping it for years behind closed doors under a plastic sheeting.

If your body gets sturdy and strong, it’s fun to take advantage of its new abilities. To test it to its limits. It feels like stepping on the accelerator of a high-performance car on a motorway.

Also, I believe that a person’s character can be developed and nurtured. And it is good for them to be exposed to such voluntary stresses from time to time. For example, I can say that the marathon completely overloaded my psyche and freed me from the stress of a work-related issue that had plagued me for three weeks before.

Finally, I really enjoyed taking part in an event of thousands of people. And to feel like a part of this great nation of runners, even though I was right at the tail end of it.

In the last lines of my letter-text I would like to encourage readers to do the walking and warn them against striving to repeat my feat. Otherwise, as stated above, you may fall victim to the “Survivors’ Mistake” and this is fraught with sad consequences for those who commit it.